The below is posted with a one day lag. (it was part of the application process for a freelance/contract writer position).

American ExpressTo participants of the capitalistic system American Express (“

AmEx”) needs little introduction. The firm is a global payments, credit card, and travel company whose products are catered to well-heeled clients.

AmEx runs one of the most prominent credit card networks in the world; unlike its largest rivals Visa and

Mastercard, however, it profits from the entire economic cycle of issuing the card, swiping the plastic (via the merchant fees), other fees, and the spread on loans it provides. It is an economic powerhouse but is subject to greater volatility because of its risks of operating such a full cycle network.

As a somewhat mature company it “has sought to return at least 65% of the capital it generates to shareholders as a dividend or through the repurchase of common stock,” a goal it has since tempered as a result of the strings attached with money it has taken from Uncle Sam. A more muted target, though impressive nonetheless, of 20% return on equity, is now the company’s goal on account of higher charge-off rates and higher capital requirements.

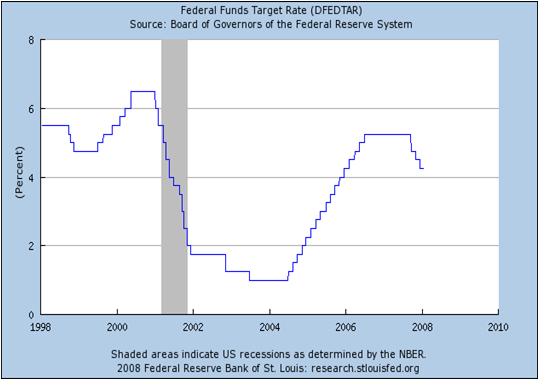

In 2008 the company grew revenue 3% year-over-year to the impressive sum of $28 billion. This is possible through its boastful network of 92.4 million cards, an industry leading high-

FICO-score client base, and ultra-low costs of funds of 3.63% for long-term debt and 2.11% for short-term borrowings.

My unofficial mentor, Warren

Buffett—through Berkshire Hathaway—has maintained his position as the largest shareholder. That’s not to say the stock is without risk. A few of

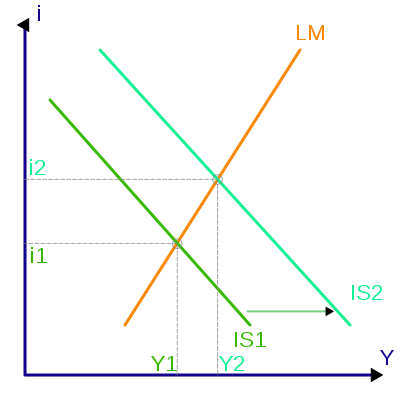

AmEx’s risks and uncertainties include: legislation on interest rates would adversely affect the company’s spread (interest charged vs. cost of funds); a really-bad-case-scenario in the macro environment would result in an even bigger spike in the charge-off rate (currently at 8.7%); a longer-than-expected turnaround in the

securitization market would force liquidity issues.

Furthermore, at 407 pages, the 2008 10K is long enough to discourage even the most determined annual report aficionados. But the audit report looks clean and the numbers don’t look funny.

ValuationSo what is

AmEx worth? Cash flow from operations has historically been 2-3x net income, largely due to the non-cash charge for the provision for losses. I use the more conservative net income as a base. The economy is in “shambles” as

Buffett has stated, and a greater portion of the world’s citizens may continue their indifference towards paying their bills. Earnings multiples should be applied with caution since these are truly extraordinary times. Even with a 50% haircut off of last year’s net income, the stock trades at close to 12x earnings, or an 8% adjusted earnings yield (the inverse of P/E ratio)—it currently has a 5.9% dividend yield while paying out only 1/3 of earnings. This is a conservatively adjusted value and reflects the erosion of

securitization income ($1

bn in 2008) and a marked increase in the charge-off rate.

The Bottom LineAmerican Express has inched its way up to the 11

th spot in

CoreBrand’s brand ranking survey of 2008 and is 15

th in

BusinessWeek’s 2007 ranking. Translation to the card user: If you get charged $1000.00 for a breakfast at a

café in Peru, you can trust that

AmEx will fight to reverse the charges. It is the antithesis of the IRS. That business moat is hard to replicate. The company is positioned to profit from the long-term demographic trend towards a cashless society. That said, the brand value, and the attractive adjusted earnings multiple, provide an adequate margin of safety. I rate American Express a “buy.”

-----------------------

P.S. 500 words (about the length of this piece) is a very short space to try to describe and dissect a business.

Disclosure:The author has an

AmEx card but pays off the balance every month. He also owns shares of

AXP.