As all writers of anything finance-related, I feel compelled to comment on housing’s role in our current economic crisis and end with the clichéd "lessons learned" bit.

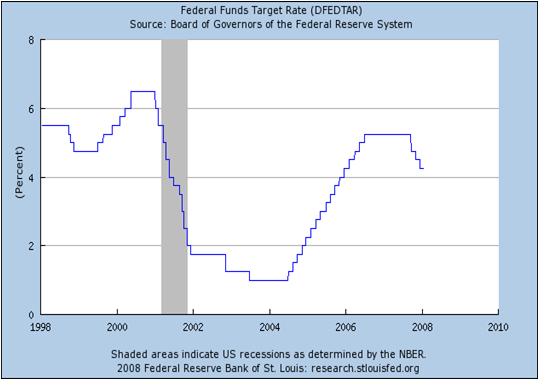

It’s tempting to say we all foresaw this. There is no doubt that housing was and is a critical part of our deep economic malaise. The seeds were sewn through low interests rates, poor lending practices, and the cultural notion that a house is more than just a roof over one's head. Though it can be more, speculative short-term gains in residential real estate should never drive a rational person’s decisions.

On the housing bubble, there are two predominate ideological camps: 1) it's the banks' fault; 2) it's the home buyers’ fault.

The first group feels the home buyers were unsuspecting victims, preyed upon by Mr. Burns-type lenders: greedy, cold, and with a profit-only code of ethics. (Not all bankers are like this, but it makes for good imagery). These bankers were eager to rush loan approvals to hasten the securitization process whereby ensuring private school tuition, vacations in Bora Bora, and early retirement. Bankers should be punished, regulated, and striped of the compensation that Croesus himself would envy.

Banks

are greedy. Their fees

are high, and certain aspects of their businesses

need to be regulated (OTC options come to mind). But they do, however, provide a valuable service to the economy. Credit drives our economy. Anyone who’s been granted a loan will attest to that.

The other group believes the home buyers themselves are to blame. Stories of credit-less deadbeats buying multiple houses with the idea of flipping and becoming wealthy, draw the ire of penny pinchers. These reckless borrowers collectively failed to notice the bubble-level home price to median income (the PE ratio of homes) ratio. Somewhere down the road, it would have to correct. They deserved their prize; they too were greedy. The modern corporation does not hold a monopoly on unethical behavior. After all, this is capitalism, and individualism rules.

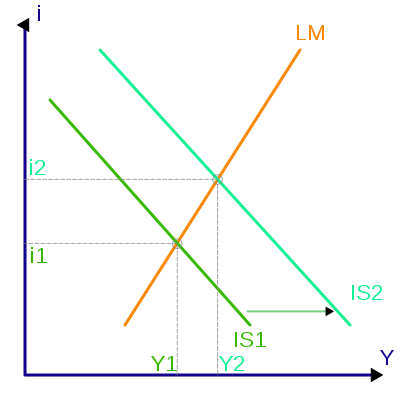

To mend the housing and credit problems there are no easy solutions. I have no idea which items of the current "stimulus bill" will have the greatest multiplier effect. I only hope that government behaves better than in times past.

Understanding this, however, isn’t the real issue from a personal learning point of view. Financial manias and asset bubbles will reappear. They are “Black Swan” events.

The real value in having lived through 2008 (and beyond) is not learning how we can personally predict (and prophetically time) any future crises, but to examine it from the most micro of human levels. What do these events tell me about how I should shape my behavior and views?

At the risk of being too prescriptive, something that I loath about most business books, I offer advice to my children and future grandchildren.

In anything in life, if there are no significant barriers to entry, it's not worth doing. Medicine requires smarts and time. Athletics begs time and talent. Business demands good ideas, execution, and drive. Anyone could set up a mortgage brokerage business and undercut the professional and legitimate players through lackadaisical lending standards. The barrier to doing it right is ethics, work, and patience. Most don’t have all three.

Lastly, (and not that there are only two, but because two are easier to remember) the further you separate the risk taker from the actual risk bearer, the more likely you are to face an unsavory result. A father, through no intermediary, should know and trust his future son-in-law. Bankers should know and trust borrowers.